“Stepping Down” Your Exercise

As physical therapists, we’re pretty good at making things harder for our patients – increasing weights, reps, changing body positions from sitting to standing to standing on one leg, or taking patients up through the developmental sequence.

I’m not so sure we shine when it comes to making things easier, or “stepping down” an exercise. In a perfect world, we meet the patient where they are physically, based on our evaluation, and challenge them to step up a notch. This is how we help make them stronger, better balanced, improved endurance, etc.

What about those patients who can’t do what you are asking them to do?

In my experience as a private practice owner, I’ve seen young therapists (but not always only the young ones) come in and start patients out a much higher level than the patient is ready to attempt. An example is having patients step over hurdles. A gentleman in his early 80s was being supported by a PT with a gait belt, arm wrapped around his back and the other arm holding his hand while he attempted to step over the hurdles. Essentially the therapist was supporting him as he leaned into her. This patient couldn’t even stand unsupported and weight shift side to side, forward/backward, or diagonally independently! While crossing over those hurdles may have been good for his ego, I highly doubt that it was actually providing him with any worthwhile “stepping stones” toward improved gait or balance. (No pun intended).

It’s Not You…It’s Me

If a patient is completely unable to perform the exercise we are demonstrating, we need to ask ourselves, “Is it them, or is it me? Is this an appropriate exercise that will help them achieve the goals we have set, in a reasonable amount of time? And will it allow us to “step up” to the next level to challenge them? Or have I chosen an exercise that will be useless in the long run, frustrate the patient, or worse yet make them more fearful?

We all want to feel good about ourselves. Sometimes choosing an exercise that is too easy so that the patient demonstrates mastery fairly quickly, in terms of technique, posture, timing, etc., can be just the right dose to provide confidence, motivation, and a general feeling of pride. I’m not saying we should always make it easy on our patients. Ultimately, we need to use our training, skills, experience, and intuition to concoct the perfect potion to help our patients be successful and return to the life they deserve.

One of the best exercises I learned in the CEEAA (Certified Exercise Expert for the Aging Adult) program was called the “Modified Single Leg Stand.” It involves standing on one leg with the other hip externally rotated, ball of foot on the floor and heel touching above the medial malleolus of the stance leg. When I was teaching one of our Bone Strong Seminar courses and demonstrated this stand, one of our participants yelled out, “Oh we do that at our clinic. We call it The Kickstand!” And so, it has become The Kickstand in my world. It is perfect for those patients whom you try and try to get to single leg stand but they just keep falling to the side, putting their foot down. I feel like I could work on this until the cows come home and they will never be able to do it hands free. This is the perfect “stepping down” option. Once they’ve mastered it with eyes open, we go to arm swings, head turns, eyes closed, compliant surface, use of upper extremity resistance bands, and so on before we step them up to Single Leg Stands.

The options are endless.

So, the next time your patient is struggling to do what you are asking of them, take a minute to see if you can slightly adjust the exercise to step it down to their level, help them gain mastery, and then step them back on up!

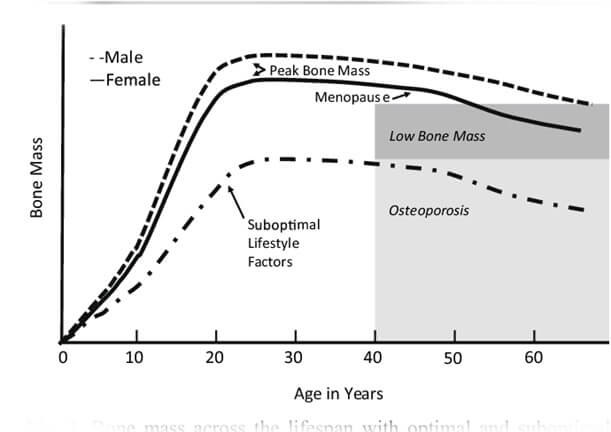

called the “silent disease” because often people don’t know they have it until they break a bone. And even then, compression fractures are painful only 20-30% of the time. Old fractures are often found on x-rays when a person is imaged for illnesses such as pneumonia. According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation,2 about one in two women and one in four men over the age of 50 will suffer a fracture due to bone fragility. At this point in time, it is estimated 80% of patients entering Emergency Departments with a fragility fracture (a fall from a standing height) are never followed up for care.

called the “silent disease” because often people don’t know they have it until they break a bone. And even then, compression fractures are painful only 20-30% of the time. Old fractures are often found on x-rays when a person is imaged for illnesses such as pneumonia. According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation,2 about one in two women and one in four men over the age of 50 will suffer a fracture due to bone fragility. At this point in time, it is estimated 80% of patients entering Emergency Departments with a fragility fracture (a fall from a standing height) are never followed up for care.